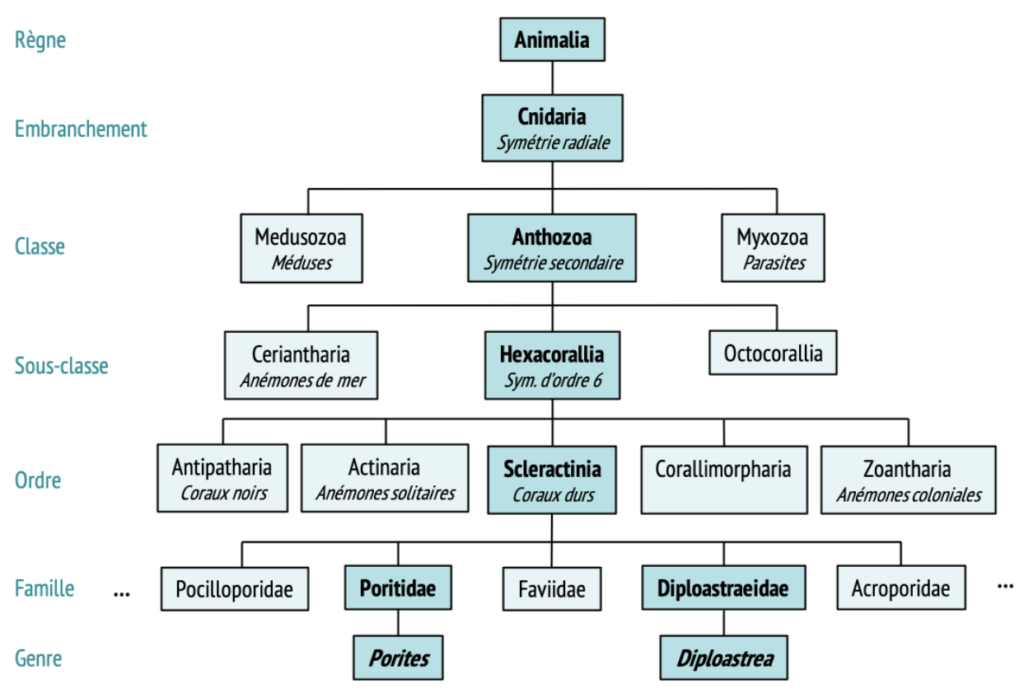

Scleractinian corals

Corals are marine animals of the Cnidaria phylum (Verrill, 1865), characterized by the presence of stinging cells called cnidocysts, and of the Anthozoa class (Ehrenberg, 1834), characterized by a secondary symmetry superimposed on the radial symmetry of Cnidaria. The “hard” corals of the order Scleractiniaria (Bourne, 1900), which belong to the subclass Hexacoralliaria, are unique in that they have 6th-order symmetry (or a multiple of 6), in addition to bilateral symmetry.

Simplified phylogeny of scleractinians (from World of Register Marine Species). Source : Marine Canesi – PhD.

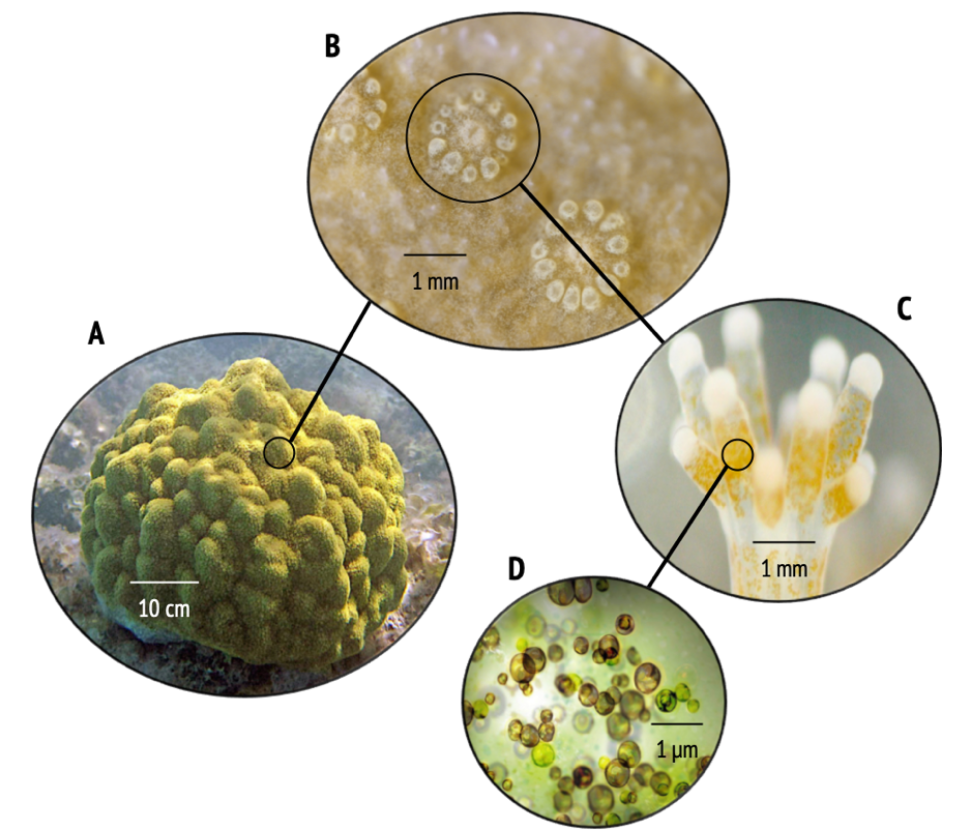

(A) Photograph of a coral colony of the Porites genus, (B) top view of a polyp, and (C) transverse view of a polyp and (D ) enlarged view of the unicellular microalgae (zooxanthellae) located in the polyp tissue. Source : Marine Canesi – PhD.